U.S. Trails in College-Graduation in Global Study

•

•

Madeline Will, Reporter

Lag also cited in preschool enrollment

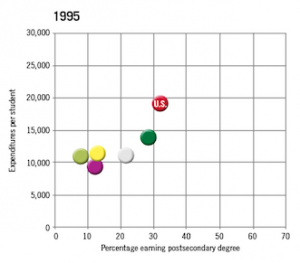

The United States has fallen behind many of the world’s leading economies in the rate of college completion, new data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development show.

According to the Paris-based OECD’s “Education at a Glance 2014,” an annual report that came out last week and compares education data for the 34 OECD member nations as well as some additional countries, the United States has the fifth-largest proportion of adults, ages 25 to 64, with a college degree: 43 percent.

But in other countries, the higher education attainment rate is growing much faster, and in some countries, surpasses the United States’.

For example, 44 percent of 25- to 34-year-old Americans have a college degree—the 12th-highest proportion and 5 percentage points higher than the overall OECD average. Meanwhile, 42 percent of 55- to 64-year-old Americans have a college degree, topped only by Canada, Israel, and the Russian Federation.

State and federal policymakers are focusing increasing attention on the rising cost of—and access to—higher education in the United States. The direct costs of college, such as tuition, to students in the United States are the highest among all OECD countries, the study found.

Only 30 percent of Americans ages 25-64 who are no longer students have attained a higher education status than their parents. Just three other countries surveyed—Austria, the Czech Republic, and Germany—had a smaller percentage, according to the study data.

Andreas Schleicher, the OECD’s director for education and skills and the special adviser on education policy to the secretary-general of the OECD, noted in a briefing last week that one reason fewer U.S. students attain more education than their parents is that more parents already have a college degree. Still, almost 20 percent of U.S. adults attained less education than their parents did.

Early Education

Across the OECD-member countries, early-childhood-education enrollment has increased, partly because of increases in the numbers of women who work outside the home and who bear children later in life.

But the study shows that the United States continues to lag behind other countries in early-childhood education, despite the fact that it ranks fifth among OECD countries in spending per pupil at that level.

Only 66 percent of American 4-year-olds were enrolled in early education in 2012; the OECD average was 84 percent. For OECD countries in the European Union, the average was 89 percent.

France and the Netherlands led the world in early-childhood participation rates for 4-year-olds, with 100 percent enrollment. Despite state and federal policymakers’ focus in the United States on increasing access to high-quality early education for 3- and 4-year-olds, the 2012 data show a slight decrease from 2005, when 68 percent of American 4-year-olds were enrolled. In comparison, the OECD average in 2005 was 79 percent.

Melanie Anderson, the director of government affairs at Opportunity Nation, a national campaign of the nonprofit Be the Change Inc., with offices in Washington and Boston, that aims to expand economic mobility and close opportunity gaps among children, said high-quality early-childhood education improves the chances for children to succeed later in life. American society, as a whole, values preschool more than it did in previous decades, she said.

While preschool enrollment has significantly increased in the United States since the 1970s, Ms. Anderson said the recent small decline may be due to a decrease in public funding.

Other Findings

The United States was one of only six countries to cut public spending for education from 2008 to 2011. The United States cut spending by 3 percent, lower than the other five, which are Iceland, the Russian Federation, Estonia, Italy, and Hungary.

The United States spent 6.9 percent of its gross domestic product in 2011 on all levels of education combined, higher than the OECD average of 6.1 percent.

Mr. Schleicher said that, overall, it is a good sign for education that most of the 33 countries with available data increased or kept the level of public spending the same during the global financial crisis.

Another key finding that has remained consistent with previous years’ reports: Teachers in the United States spent more time teaching than their peers in almost any other country (with available data)—amounting to more than 1,000 hours teaching in the classroom. Still, U.S. teachers’ salaries are not competitive and, for primary and lower-secondary teachers, have not increased since 2005, the study found, unlike the salaries for many of their international peers.